The dangers of arterial endofibrosis

Never heard of it? Neither had we but it's a disease that regularly affects cyclists and it's always good to be in the know.

Cycling is something we do because we love it, and it’s a huge plus that there are so many health benefits of regular aerobic exercise. These hidden benefits – reduced incidences of hypertension, heart disease and chronic conditions such as diabetes – are the reason many people begin to ride a bike again in later in life. But did you know that in a percentage of young, healthy individuals, cycling puts them at risk of a vascular disorder that can have devastating consequences?

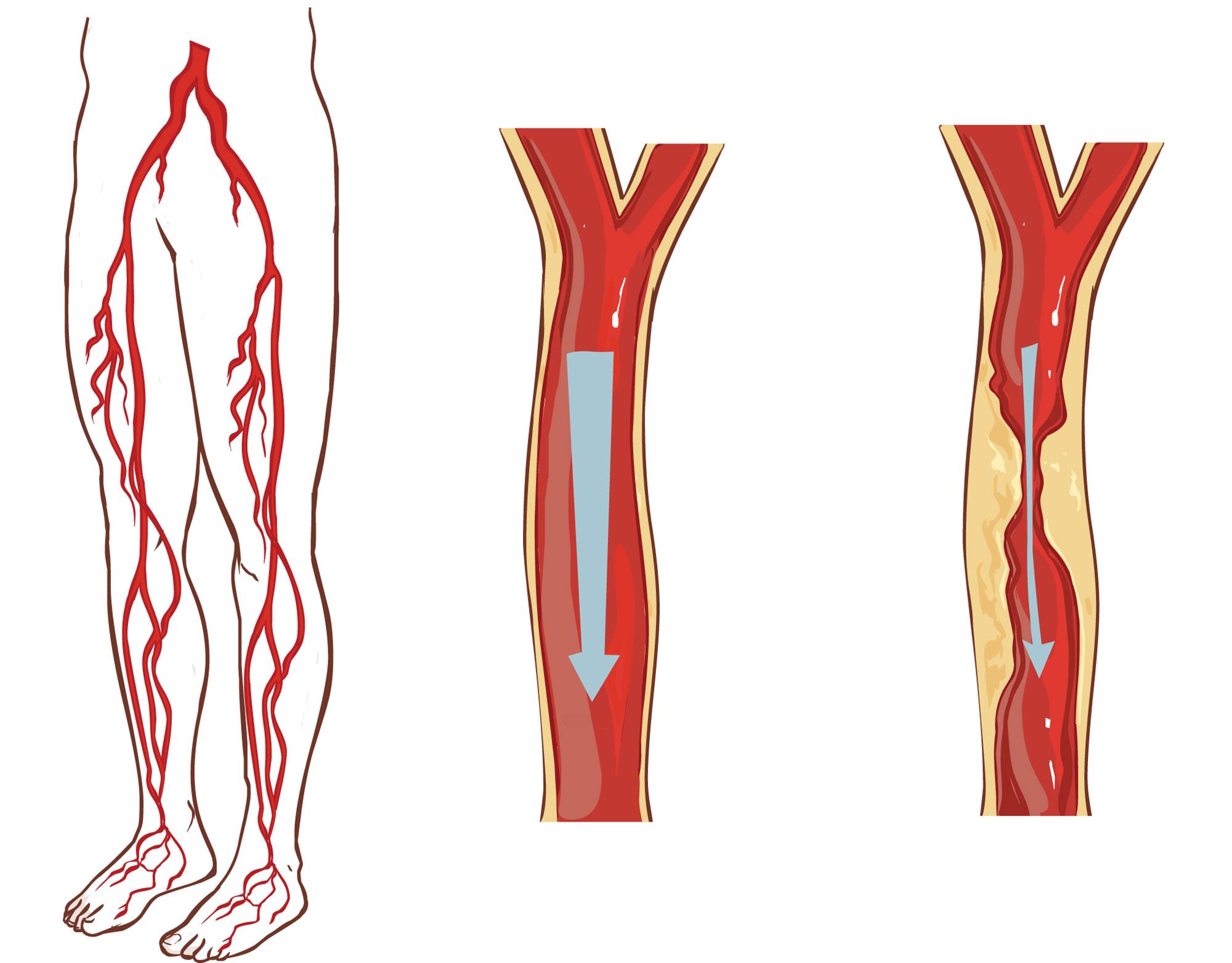

External Iliac Artery Endofibrosis (EIAE) is a rare disease, which is increasingly common in cyclists and endurance athletes, and could be attributed to 10 to 20 per cent of leg symptoms in competitive cyclists. Though the exact pathogenesis is unclear, endofibrosis is essentially the thickening and deposition of collagen within the artery from a repetitive inflammatory process, resulting in less arterial compliance, arterial stenosis (or narrowing), and reduced blood flow which can lead to neurological-type symptoms. For cyclists, this can mean weakness, numbness, burning, pain and loss of power to the affected side.

The external iliac artery is the artery providing perfusion – or blood supply – to the lower limbs, bifurcating or splitting from the aorta in the lower abdominal region. There is a right and left external iliac artery, and commonly athletes with the condition will only be symptomatic on one side.

Unlike other vascular problems, EIAE isn’t believed to be related to atherosclerosis – the more common vascular disease which is main agonist of cardiovascular disease and ischaemic stroke. Rather, it affects young, healthy individuals with endurance sport backgrounds, and it is claimed that the condition could be caused by a number of factors. These include: genetics (length and location of the artery); an aggressive flexed-at-the-waist cycling position that ‘kinks’ the artery; high blood flow rate during intense exercise; and even muscular compression (psoas). However, there is no singular definitive causation at this stage.

It’s important to note that EAIE is usually exacerbated by higher intensities, so while long slow rides and recovery-paced potters may not elicit symptoms, the problems most commonly appear when it’s time to crank up the noise training in higher zones.

But how would you know if this is something you are suffering from? Former professional endurance mountain biker Matt Page knew something was wrong on the bike when he began to lose feeling in his left leg during harder efforts. “High intensity races such as cross-country road races and hill climbs became unviable,” he explains.

Former professional road racer Stuart O’Grady also suffered with the condition until he sought medical attention in the early 2000’s, resulting in surgical intervention and a month off the bike. He recovered and subsequently claimed a famous win in the 2007 Paris-Roubaix, as well as Olympic and Commonwealth gold medals.

Getting a correct diagnosis can be tricky and many doctors would perhaps not consider EIAE in a young active person complaining of loss of power in their leg. But if you are concerned about EIAE, don’t hesitate to consult a sports doctor or raise the issue with your GP. There are a number of maximal effort tests and imaging processes that can lead to a diagnosis and treatment pathways.

As cyclist Matt Page says: “Don’t try and guess the problem – if you have any numbness or weakness in one leg then get it checked out.”

Words: Anna Beck Photo: Tim Bardsley-Smith