We can all agree that mountain biking isn’t just physical; it can sometimes be just as challenging mentally. Below, I’ll touch on the role setbacks can play in one’s career, how to deal with emotional regulation, and how our core motivations play into it all.

For many, mountain biking is about the process the bike takes you on. We all get into it for different reasons but ultimately for the same common goal: satisfaction. Like anything you’ve started in life, there is always that desire to improve that sneaks in at some stage along the way. And while this progression may take different shapes for each of us, that desire is always there. Finding that limit into a corner, going further into the backcountry, or finally getting out the bike as much as you want will always be one of the purest feelings. The rush from any one of these things is something you can’t quite explain to someone.

The other side of the coin to progression is setbacks. Mountain biking can be an incredibly humbling undertaking if you ever want to improve. There is nearly always someone faster, fitter, or more skilled than you.

Being in touch with your own personal emotions and motivation is key if you are willing to progress without negative pressures and is key to protecting your love for the ride.

Emotionally negative events have more impact than positive ones, and this ‘failure’ can be attributed in a variety of ways to different factors – often swayed by a self-serving ‘attributional bias’. This means that most of us tend to attribute reasons for success to internal, stable factors, i.e. based on our own ability. On the other hand, our failures are often attributed to external and unstable factors like bad luck or misfortune. By changing our thinking and honestly attributing these negative moments without emotional influence, we can lay the foundations for the comeback. This can also act as motivation.

It’s not just weekend warriors; even the sport’s elite struggle to attribute setbacks. The 2022 DH Overall World Cup Winner, Amaury Pierron, broke his C5 vertebrae in 2023 after crashing into an unprotected stump in the B-zone.

Disappointed that the stump wasn’t padded for safety, he posted his frustration to Instagram, externally attributing his misfortune to the unsafe track. Asking ‘what-if’ is understandable in these moments, but the mental battle is to balance this with internal attribution and accept his part in the accident. This internal attribution style is integral to finding the motivation to bounce back. There is little doubt that Pierron’s extraordinary return required the mental discipline to overcome the setback and rebuild his strength and confidence. It has been great to see him make his way back to the top of the sport with ridiculous, back-to-back winning margins in Val di Sole and Les Gets less than one year later.

Attribution of failure and setbacks is at the forefront of emotional regulation. These negative moments can take shape in various ways. If you’re a committed racer, having a run filled with mistakes will leave you ruminating. For others, this may be provoked by a simple crash, a mechanical, or not being organised enough to make time for your weekly ride.

While it can be individual, pleasant emotions usually lead to increased performance, and negative emotions can cascade to a series of performance decay. In the case of a crash, there’s nothing worse than thinking about the last time you rode and the slide-out you had in a turn. And while some of us may think about techniques involving body positioning when out on our regular rides, the mental side of it all is often overlooked. The attentional bias of thinking about the crash inherently increases the chances of another crash.

A Case Review: Getting Jon’s mojo back

I considered all this when out for a pedal talking with my mate Jon Edwards, whose name you may know if you are around the race scene in Queensland. He is pinned on the downhill bike and has pushed himself hard to progress to race at the highest levels, most notably Crankworx Whistler last year. Equally, Jon always just looks to be happy on his bike, having more fun than most I know.

Last year, Jon spent the summer working in Colorado at a bike park to enjoy as much time riding his bike and find the pace needed to compete. While his main motivation was just to enjoy the ride, goals of racing Crankworx Whistler and a US downhill rounds were definitely front of mind.

Fast forward to Whistler; The iconic ‘1199’ track has everything. Fifteen-metre drops, steep rock slabs and loam sections linking it all together pose a harrowing task for any rider. Struggling with mechanicals, Jon felt unprepared heading into qualifying and had a rough run. Despite his bad run of luck, he largely attributed most of this to himself and set his focus on race day. Jon said being among the first to drop in was exciting and lifted some pressure off him. Being around some of the elites of the sport had him stoked and he managed to have a calm mindset after the previous day’s troubles.

With an incredible crowd on the hill, Jon described it as the wildest run ever, with many loose moments. Though off the pace of the big names of downhill, he was able to put down a personally satisfying run. The experience gave him a taste of racing at the top and a better idea of where he was at before returning home. The composure of the elites at the top before dropping in was definitely something that he noticed.

But the ability to race with the best didn’t come without setbacks. Late in 2022, Jon suffered a severe concussion and T7 compression fracture out on his local trails. He broke his wrist at Cannonball earlier this year just before heading overseas. More recently, he dislocated his elbow. Mix in a few hefty concussions, and he’s struggled to find a consistent spell of good health over the past two years.

Initially, Jon took an avoidant approach by ‘trying not to care’ about these injuries, but he has since reverted to taking it slower and moving step by step. He finds his progression gradual, and he needs to be surrounded by the right people and keep his motivation coming from the right place.

These injuries and his love for racing, combined with his internal attribution style, haven’t been without their struggles. Recovering from these injuries and trying to pick up where you left off comes with a lot of work, to the point where, at times, Jon felt that riding – once his outlet – was becoming stressful and challenging to navigate.

Since then, he’s opted to find a balance between his racing efforts and his future career, studying mechanical engineering, which offers exciting opportunities.

Kirk McDowall has had similar experiences. A lead engineer for Norco in developing their downhill bikes and already a decorated downhill athlete, McDowall found his way back onto the team and has had a strong season. Kirk seems to have found a healthy balance between professional life and racing.

Jon hopes to find that balanced mindset, with this new bike-adjacent focus easing some of the pressure he was putting on his racing. Jon can put his heart into racing knowing that he has another passion of his waiting, should it not work out.

The point of all this is that the manner in which Jon has taken these setbacks in his stride is a testament to his dedication to his racing. As he explains, his main motive for riding is to have fun, but he will always have that deep desire to go as fast as he can, describing racing as a part of him.

Ultimately, Jon identified his emotional regulation as something he could definitely improve, as I’m sure we all could. Regardless, he knows that some simple breathwork before dropping in works wonders for him. His deep-rooted motivation and love for riding keep him coming back and returning to form despite the stress and doubt surrounding his injury.

Mental Strategies and Brain Hacks to Improve Your Riding

So how can these concepts help you?

As mentioned, motivation is key to emotion. Understanding why you ride will help you understand why you feel this way about obstacles. If a feature gives you stress and you are avoidant, maybe that isn’t why you ride.

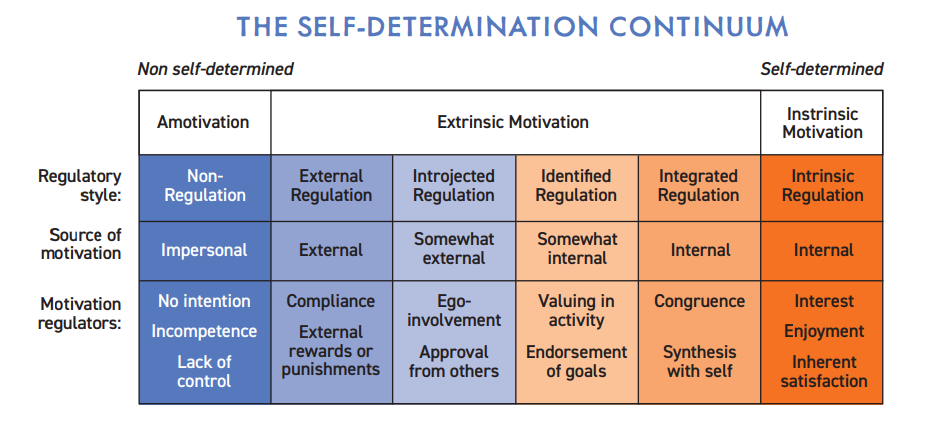

Reading about the self-determination continuum could help you understand your own strivings. Are you hitting this new feature to feed the ego (introjected motivation), or is it out of a genuine desire to improve (intrinsic motivation)? Closely related to this, understanding your attribution tendencies in relation to your motivation is key to unlocking why you feel certain ways.

Once in touch with your motivations and desires, emotional regulation is the next step. One approach is the ‘Process Model of Emotion Regulation’, focusing more on the stimuli than the emotions themselves. It includes 5 steps:

- Situation selection: avoiding specific situations e.g. a section of track.

- Situation modification: changing the situation to be more comfortable e.g. approaching a section of track with someone who has done the feature before.

- Attentional deployment: breaking the section down into parts and focusing simply on what needs doing.

- Cognitive change: recognising the emotions and acknowledging it is part of the situation, eg acknowledging the risk and making a judgement based on that.

- Response modulation: finding your optimal state of arousal. Calming arousal could involve breathing techniques, progressive muscle relaxation, or meditation. Arousing may involve breathing techniques as well, or potentially music and warm-up exercises. These vary massively individually, and many people often establish set routines or verbal cues to get to that ideal level.

At the elite level, these ideal performance states of arousal are extremely relevant. Understanding the positive and negative emotions you feel and how they influence performance is key. As mentioned earlier, generally, positive emotions are better, but some ‘negative emotions’, such as aggression, can be beneficial; this is mostly down to individual differences. Alternatively, being excited or overstimulated can often result in peaking too early or not being grounded enough to perform well.

While not many of us will have the opportunity to break the gate at the top of a World Cup Downhill or even crush the ‘1199’ in Whistler, many of us seek progression on the bike in individual ways. By employing some emotional regulation techniques and finding our own source of motivation and balance between different aspects of our lives, we can continue to seek our limits in a healthy way.